What is Pulmonary Hypertension?

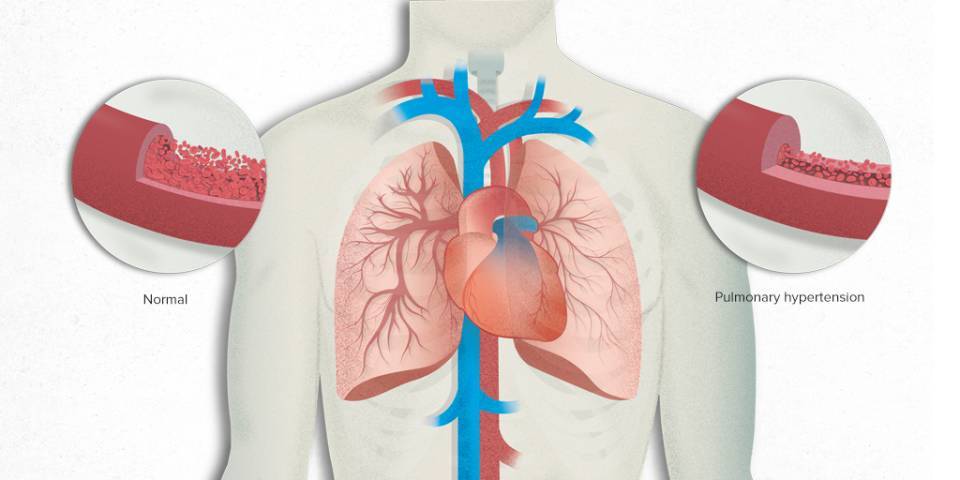

Pulmonary hypertension is the abnormal increase in blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries.

This increase in pressure can be produced by various mechanisms. The most common are chronic heart and respiratory diseases. However, pulmonary hypertension can also occur due to diseases of the pulmonary arteries themselves or from obstruction by blood clots that become chronic. All these situations and mechanisms represent an overload for the heart in its function of pushing blood to the lungs.

As a result, people who have this disease feel tired, dizzy, have palpitations or are short of breath, among other symptoms. Over time, overloading the heart can lead to heart failure. The pressure in the pulmonary arteries can be measured directly only with an invasive test: right heart catheterisation.

The main symptom of pulmonary hypertension is dyspnoea, which is a feeling of shortness of breath when exerting oneself

To someone who has just been diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, what I would say first of all is you need to be patient and very resilient.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is considered to exist when the mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) is greater than 20 mmHg and the pulmonary vascular resistance is greater than or equal to 3 mmHg/L/min.

Pulmonary hypertension can occur from many causes. Depending on its features and origin, the disease can be classified into several groups. Therefore, there are differences in the treatments and in the follow-up of affected people.

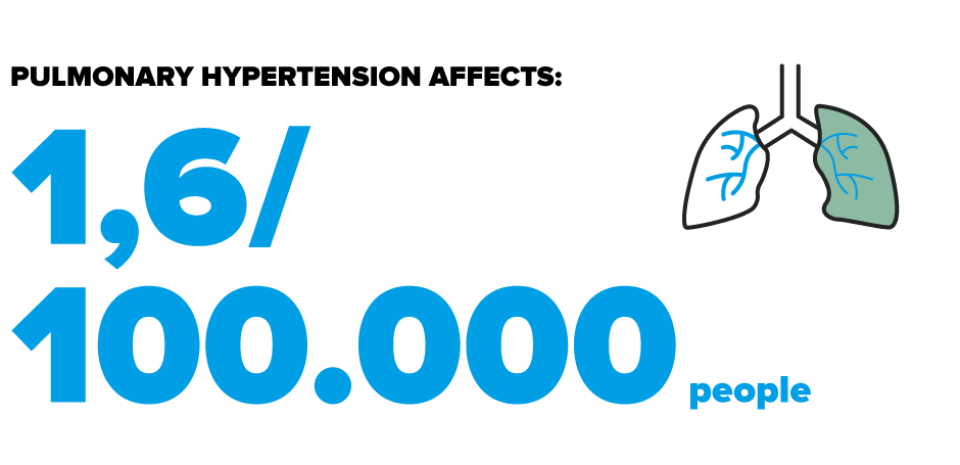

How many people are affected by Pulmonary Hypertension?

Pulmonary hypertension secondary to chronic heart or respiratory diseases is common. However, the most severe forms of pulmonary hypertension occur due to a specific disease of the pulmonary arteries, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). These are rare diseases, which have a specific approach and treatment.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is rare. Its prevalence in the general population is estimated at 1.6 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and its incidence is estimated at 3.7 new cases per million inhabitants per year. The disease usually occurs between the ages of 30 and 40 and is more common in women.

The prevalence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is estimated at 0.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and its incidence at 0.09 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. Approximately 2-3% of acute pulmonary embolisms can progress to CTEPH.

Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension

The clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension has varied over time. According to the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension, it is divided into five categories:

-

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

-

Pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease

-

Pulmonary hypertension associated with respiratory diseases and/or hypoxaemia (oxygen deficiency in the blood)

-

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

-

Pulmonary hypertension of unclear or multifactorial cause

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is caused by an occlusion of the pulmonary vessels by blood clots (thrombi). Unlike pulmonary arterial hypertension that affects vessels smaller than 300 μm, CTEPH can affect larger vessels, and in these cases it can be treated surgically. Right heart failure and death are consequences of CTEPH if patients are not treated.

The symptoms of CTEPH are intermittent and occur when more than 60% of the pulmonary circulation is affected. Exercise intolerance and breathlessness are common symptoms, along with fatigue, chest pain and recurrent loss of consciousness during exercise or coughing. Coughing up blood (haemoptysis) and vertigo can also occur.

The evolution of CTEPH is episodic with prolonged periods called "honeymoons" when the symptoms are mild or non-existent. In general, the evolution is more variable than that of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

In recent decades, pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) has been considered the best treatment for this disorder. It has shown very low perioperative mortality (less than 5%), excellent quality of life and, in favourable cases, normalisation of exercise capacity and haemodynamic parameters at rest.

Related contents

Substantiated information by:

Published: 23 November 2021

Updated: 1 December 2021

Subscribe

Receive the latest updates related to this content.

Thank you for subscribing!

If this is the first time you subscribe you will receive a confirmation email, check your inbox