Treatment of Hypercholesterolaemia

The need for treatment to reduce cholesterol levels must be individualised to each person and largely depends on the risk of suffering a cardiovascular event (heart attack or stroke).

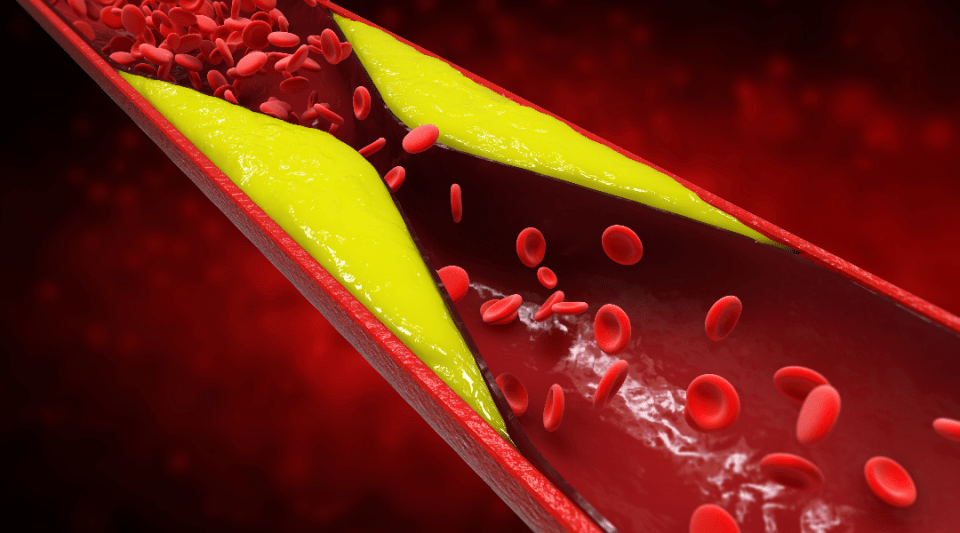

All patients who have previously experienced a cardiovascular problem should receive cholesterol-lowering treatment, regardless of the levels they had before the event: this is known as secondary prevention treatment. In this case the aim of the treatment is to lower the risk of another cardiovascular event, as reducing cholesterol is a common protective element for improving the state of the damaged arteries, whether due to tobacco, high blood pressure, diabetes, cholesterol or a combination of these or other risk factors.

To evaluate the need for treatment in people who have not suffered a cardiovascular problem (primary prevention treatment), each individual’s overall cardiovascular risk must be assessed, and a decision made accordingly.

Once it has been decided to start treatment to reduce cholesterol levels, the recommended values to reach in order to prevent cardiovascular problems must be determined. These are known as cholesterol targets. These are usually established as LDL cholesterol figures.

The target varies depending on whether or not the patient has previously had a cardiovascular problem (secondary or primary prevention, respectively). In the case of primary prevention, the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk level is also taken into consideration. These objectives depend on whether the person has had a cardiovascular problem previously or not (secondary prevention or primary prevention, respectively). The target for people who have had a cardiovascular problem is to reduce LDL cholesterol to 55 or at least 70 mg/dl.

That is why it is important to know the treatment control targets right from the outset. In some countries, above all Anglo-Saxon countries, less importance is placed on the LDL target values and greater consideration is given to the type of treatment the patient should follow.

Maintaining an active lifestyle, physical exercise and a healthy diet are associated with better control of blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels. In addition, achieving and maintaining a total amount of adequate body fat (by preventing or treating excess weight and obesity) and stopping smoking have benefits for cardiovascular health.

Diet. The Mediterranean diet is known for being plant-based: rich in fibre, whole grains, fresh fruit, various vegetables, legumes, nuts and extra virgin olive oil. This diet has proven beneficial for levels of cholesterol and triglycerides and for reducing cardiovascular diseases. Food must be low in saturated fats (replace with unsaturated), salt and added sugar (both present in processed products); while avoiding sugary drinks and prioritising the consumption of fatty fish over red or processed meat and ultra-processed foods.

Weight. Avoiding the excess weight that occurs as a consequence of accumulating general adipose tissue or its predominance in certain parts of the body (stomach).

Physical exercise. At least 150 minutes of moderate and 75 minutes of intensive physical exercise should be performed each week.

Toxic habits. Avoid toxic habits such as drinking alcohol and smoking.

Stress. Use stress management strategies.

There are several strategies to reduce cholesterol with medicines. For instance, there are drugs that decrease cholesterol production in the liver or which enable the liver to capture or “clean” more cholesterol from the blood. Alternatively, some medicines reduce the amount of cholesterol absorbed from food or promote its intestinal elimination.

Statins. Statins are the treatment of choice and best-known drug therapy against hypercholesterolaemia. They are also the most used drug at present. This family comprises different compounds and the two most representative ones are simvastatin and atorvastatin. They act by reducing cholesterol within the liver, which means it subsequently captures more cholesterol from the bloodstream and therefore decreases levels in circulation. At high doses it can reduce LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels by up to 50%.

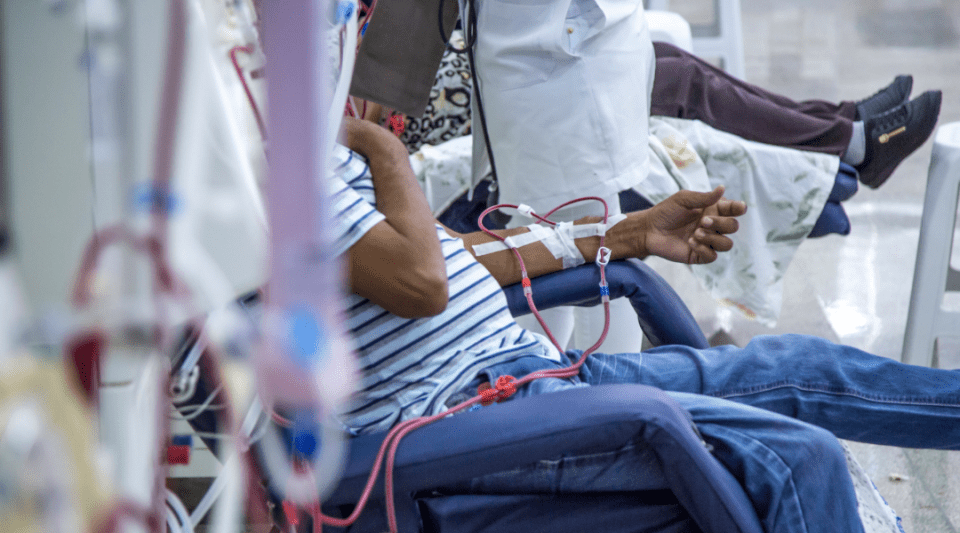

Aphaeresis. For people with serious genetic cholesterol disorders and very high blood levels, in addition to normal drug therapy or that they do not tolerate the medication, there are techniques for removing cholesterol from the blood (aphaeresis) which are similar to dialysis for people with kidney disease, but much simpler and better tolerated.

Ezetimibe. Ezetimibe acts by reducing cholesterol absorption in the intestine. It is very well tolerated and associated with LDL cholesterol reductions of 15%–20%.

Fibrates (fenofibrate or gemfibrozil). Above all these are used to decrease triglyceride levels, although they can have a discreet or moderate effect on cholesterol.

Bile acid resins. These drugs act at an intestinal level, promoting the intestinal elimination of bile, which is a substance very rich in cholesterol produced by the liver to digest fat.

Bempedoic acid. This acts similarly to statins, reducing cholesterol production from the liver and promoting its uptake from the blood. It is less potent than many statins and generally reduces LDL cholesterol figures by 15-20% when taken in isolation.

Controlling cholesterol with statins is the oldest and currently the most used treatment option. They are associated with several side effects, in particular muscle and joint problems, and they have been described as inappropriate for continuous use.

However, scientific evidence shows that the risk of significant adverse effects attributable to statins is very low. Furthermore, patients are monitored through regular blood tests and interviews with the medical team.

Long-term treatment with statins is very safe and prevents cardiovascular problems such as heart attacks and strokes, so they tend to be the first therapeutic option. The healthcare professional must inform the patient about the risk–benefit relationship associated with statins, so they can ultimately make a decision on which treatment to follow.

Treatments to reduce cholesterol are very safe and several studies have shown over many years that they lower the risk of developing cardiovascular problems. Therefore, these drugs, particularly statins, are taken by millions of people worldwide.

The reduced risk of cardiovascular events substantially outweighs the side effects that can be attributed to statins. Nevertheless, the potential adverse effects include:

Proven:

- Muscle problems. Statins have been reported to produce muscle aches (myalgia), which are easily reversed when the dose is lowered, or the drug is discontinued. Severe muscular side effects are extremely rare.

- Elevated transaminase levels (an indicator of liver damage). Although increases in transaminases observed in blood tests can be linked to statins, they are usually insignificant, uncommon and reversible. They are safe for use by patients with increased fat in the liver.

- Increased risk of diabetes. Statins are associated with a slight increase in the risk of diabetes calculated to affect 1 in every 1,000 people treated for 1 year.

Unproven:

- Memory problems. Studies have not found any relationship between the use of statins and the risk of dementia.

- Kidney problems. There is no correlation between the use of statins and a deterioration in kidney function. They can be used safely in patients with kidney failure after a small dose adjustment in some cases.

High cholesterol is not treated with surgical procedures, but rather cardiovascular problems are. Such as in the case of coronary artery or lower extremity bypass surgery which circumvents blocked segments of arteries, or stent implant surgery where a small metal cylinder is placed inside the artery to open a blockage. Some rare cases of very severe hypercholesterolaemia of a genetic character may be treated extraordinarily with a liver transplant.

As with many diseases, treatments to reduce cholesterol have advanced very notably in recent years. Some of these recent advances have resulted in approvals for several drugs belonging to the biological medicine group. Notable examples are PCSK9 protein inhibitors (such as alirocumab and evolocumab) and small interfering RNA (siRNA) drugs that inhibits PCSK9 (such as inclisiran). These act by blocking or selectively reducing the production of a substance in the liver (PCSK9) which naturally reduces the number of receptors the liver cells contain to “clean” cholesterol from the blood. When PCSK9 protein production is inhibited, the number of receptors to clean cholesterol increases, thus reducing cholesterol levels. These drugs are injected subcutaneously (similar to insulin) every 2 or 4 weeks (for alirocumab and evolocumab) or every 6 months (inclisiran). They can reduce LDL cholesterol levels by 50% (inclisiran) or 60-65% (alirocumab and evolocumab).

Given their high cost, at present they are only dispensed at hospitals and specialised centres. In countries where the public health system either partly or entirely covers the cost of medicines (as in the case of Spain), in specific situations patients can receive these drugs free of charge if their LDL cholesterol level remains high after receiving conventional treatment (at the least, potent statins at high doses). These situations are:

- Prior cardiovascular disease (heart attack, stroke or damaged arteries in the legs).

- Familial (genetic) hypercholesterolaemia.

- Either of the two previous situations when the patient does not tolerate statins, or they are contraindicated.

Substantiated information by:

Published: 2 October 2018

Updated: 21 October 2025

Subscribe

Receive the latest updates related to this content.

(*) Mandatory fields

Thank you for subscribing!

If this is the first time you subscribe you will receive a confirmation email, check your inbox