- What is it?

- Risk factors

- Symptoms or signs

- Diagnosis and tests

- Treatments

- Evolution of ASD

- Living with ASD

- Lines of research

Symptoms or signs of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are characterised by social interaction and communication problems as well as the tendency to realise repetitive behaviours. However, the symptoms and their severity can vary across these three main areas.

In some people the symptoms may be subtler and cause less impairment, especially in individuals at the very edge of the spectrum who are typically high functioning, but in others the symptoms could be more severe and individuals may be unable to develop language skills or they display repetitive behaviours that interfere with daily life.

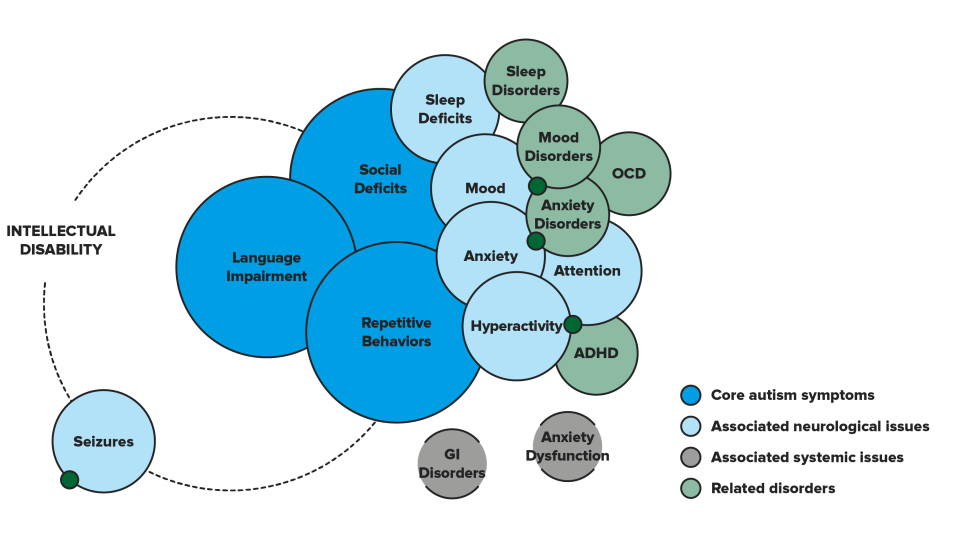

The diagram below shows how the basic symptoms of autism are usually accompanied by other diseases and disorders, which may also course with varying degrees of severity:

Children who develop normally are naturally sociable. They usually look at peoples’ faces, show an interest in voices, grab hold of fingers and even smile from the age of 2–3 months.

Problems with everyday interactions. By contrast, the majority of children who develop autism present difficulties in their day-to-day interactions. Hence, at the age of 8–10 months, they are often less interested in people, less responsive to their name and still do not babble. They later tend to experience problems playing social games, they do not imitate everyone else and prefer to play alone. Both children and adults with autism find it hard to interpret other people’s thoughts and feelings (empathy, theory of mind). This difficulty to appreciate things from someone else’s point of view may interfere with their capacity to predict or understand other people’s actions.

Difficulties interpreting facial expressions and gestures that normally accompany interaction, which means people with autism often misinterpret situations. For example, it is not the same to say to someone, “Come here!” with a smile and open arms indicating you are about to embrace, as saying it with a scowl and hands on hips because you are about to scold them. The social world becomes very hard to understand without the ability to interpret these gestures and expressions.

Emotion regulation difficulties. Such difficulties could lead to what seems to be “immature” behaviours, such as inconsolable crying or tantrums in inappropriate situations. Aggressive behaviour, against objects or themselves, is also more common in these patients. This tendency to loss control may be more frequent in frustrating situations or due to overstimulation.

By the age of three, most children can form sentences and have met all the language development milestones. Furthermore, children are expected to babble within their first year and then start using one or two words from then on, they should turn when they hear their name, indicate which objects they want or wish to show to someone. They also tend to display expressions or make sounds indicating displeasure when offered something they do not like or want.

Delay in language development and the use of gestures for communication. Children with autism tend to present a delay in language development and the use of gestures in communication. In some cases, the child presents normal development in terms of babbling and their first words in the first few months of life, but they subsequently lose these communication skills. In the majority of autistic children, language takes longer to develop and they do not start to talk until much later than expected. In other cases, they are unable to fully develop spoken language and only after intervention will they learn to communicate through other systems, such as with images, sign language, electronic processors or computerised voice generation systems.

Peculiar language characteristics. When autistic patients start to develop their language, they often have peculiar characteristics. They may find it hard to form sentences, speak with unconnected, individual words or repeat the same phrases over and over again. Sometimes patients combine these traits with literal repetition of part or all of everything they hear (echolalia).

Other children with ASD do not suffer a delay in language development (children and adults who were previously diagnosed as having Asperger syndrome), in fact they may develop speech earlier and with a strikingly rich vocabulary, but despite this they usually find it hard to maintain a conversation. For example, these children and adults carry out monologues about their favourite subjects without giving other people a chance to comment or interject. Normal conversational exchange and the incorporation of the other person’s replies are harder for these individuals. Some children with ASD and high language skills usually talk as if they were “small professors”, without changing to a more “child-like” register when talking with their classmates.

Difficulties understanding body language, tone of voice, expressions or idioms which should not be taken literally. Similarly, they may not understand irony, sarcasm or puns that form part of everyday communication.

Furthermore, people with autism do not always have normal body language skills and so facial expressions, movements and gestures may not match what they are saying (incongruence). Maybe their tone of voice does not vary, nor reflect their emotions. For example, some have a very high pitch or do not emphasise words and so they speak with a very flat, mechanical tone which sounds “robotic” (prosody alterations).

All of these communication problems can cause frustration in people with autism that could lead to inappropriate behaviours. All communication facilitation methods help increase the individual’s capacity to express their needs and feelings, while also encouraging behavioural improvement.

Unusual repetitive behaviours and a tendency to restrict interests and activities. Examples of some of these behaviours include hand flapping movements, rocking, jumping on the spot, running around in circles or around objects, repeatedly pacing across their cot or up and down a corridor.

Placing objects in a certain order, repeating sounds, words or phrases. Some of these repetitive behaviours can be self-stimulating, for example, moving hands in front of eyes. Symptoms associated with unusual responses to sensory stimuli (sensory hyper- or hyposensitivity) have also recently been included in this group of symptoms.

The tendency to participate in a restricted range of activities is evidenced by the way in which many children with autism play with toys. Some spend hours aligning them in a specific order rather than playing with them imaginatively. In the same manner, this tendency manifests in some adults as a need to maintain certain household objects or furniture in a fixed order. The most notable point is how their mood can change if something or someone moves any of these objects or the time they dedicate to the activities. People with autism often adhere to a routine in the majority of their everyday activities and even the slightest change could prove very stressful and trigger altered behaviours.

Different and highly exaggerated interests. Repetitive behaviours can also appear as highly exaggerated interests. In some cases, these interests may be very unusual and differ from those typically shared by others in the same age group (fans, car washes, traffic lights, etc.); in other cases, it may be an interest shared with their counterparts but the remarkable point is how much time they dedicate to it, accumulating a vast amount of often irrelevant information. Patients with autism often show this type of excessive interest in numbers, symbols, timetables, dates, transport routes or scientific topics.

Hypersensitivity. Abnormal responses to sensory stimuli are the result of difficulties processing and integrating sensory information or stimuli such as images, sounds, smells, tastes or movement. Autistic individuals may experience apparently normal stimuli, such as pain, discomfort or confusion. Some people with autism are hypersensitive to tactile stimuli, sounds or intense light and so they may not tolerate normal clothes, annoying sounds (hairdryers, vacuum cleaners) or being in a room with normal lighting. Hyposensitivity could mean the individual demonstrates a very high pain threshold and does not realise when they are injured, for example.

Genetic syndromes. The incidence of autism is higher in people with certain genetic syndromes that involve neurodevelopmental alterations. Some examples include: fragile X syndrome, Angelman syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, chromosome 15 duplication syndrome and other chromosomal disorders resulting from the mutation of just a single gene.

Some of these syndromes, which are associated with 15–20% of autism cases, feature a family medical background or physical characteristics that can aid in its identification. Confirmation of the genetic diagnosis can help guide the treatment, prevent or reduce associated illnesses and should be considered during family planning.

Convulsions. Seizure disorders, such as epilepsy, are present in up to 39% of people with autism. They are more common in people who also have an intellectual disability.

Autism-related seizures tend to develop at any stage of childhood or adolescence, but they can occur at any moment.

People with autism can experience different types of seizure:

- Tonic-clonic seizures. Patients lose consciousness and collapse to the ground, their body stiffens and they have muscle spasms.

- Absence seizures. These are barely noticeable because they are very mild and the only signs are often just rapid blinking or a few seconds staring into the distance as the individual appears to be momentarily absent.

- Subclinical seizures. These can only be detected during an electroencephalogram.

Sleep disorders. Sleep disturbances are very typical among children and adolescents with autism and can also affect a lot of adults. They tend to consist of difficulties falling asleep, waking up a lot throughout the night or waking up early.

Pica. This is a tendency to eat non-food substances. Eating objects that are not foods is a typical part of development between the ages of 18 and 24 months. However, some children and adults with autism and other developmental disabilities continue eating objects such as earth, clay, chalk, paint, cards, etc. It is therefore important to analyse lead blood levels in patients who persistently eat non-food substances.

Intellectual disability (ID). Between 30% and 70% of people with autism could have some degree of associated intellectual disability and so it is important to evaluate this area. The individual’s functionality and ability to adapt, which could be highly impaired even in the absence of ID, should also be determined.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The typical symptoms of ADHD overlap with some of those observed in ASD syndromes, e.g., planning and organisation difficulties (executive function). Whenever the signs and symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and poor concentration are present then the possibility of making this additional diagnosis and adapting the usual treatment for ADHD to a population with ASD should be assessed.

Anxiety disorders. These are more common during puberty and adolescence, particularly in individuals who have close relatives with anxiety disorders. They can be hard to diagnose but they must be taken into consideration in the case of deteriorating behaviour (irritability, sudden outbursts of aggression), greater apprehensive and the appearance of avoidance behaviour, or an increase in repetitive behaviours and resistance to change.

Affective disorders. Depression is also more frequent during adolescence and in patients with a family history of depression. Altered behaviours, an increased tendency towards isolation and, in general, functional deterioration in everyday activities can be signs of affective disorders.

Substantiated information by:

Published: 20 February 2018

Updated: 12 December 2023

Subscribe

Receive the latest updates related to this content.

Thank you for subscribing!

If this is the first time you subscribe you will receive a confirmation email, check your inbox

Social interaction problems in Autism Spectrum Disorder