Many media outlets shared the news about the cure of a person with type 1 diabetes, following the article published in the journal, Cell.

It is always good news to read about advances in curative treatments for diabetes. However, sometimes, the media is able only to superficially reflect the context in which this research takes place.

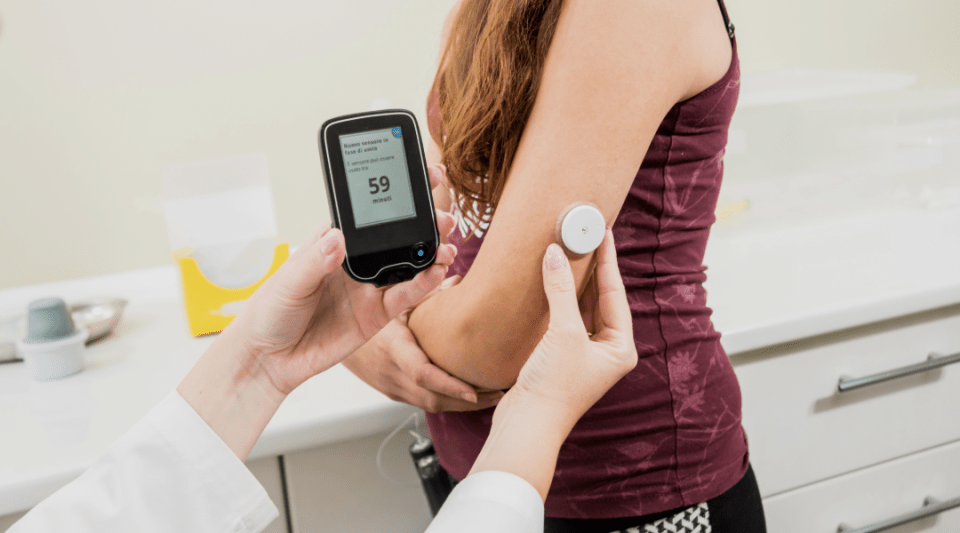

In this case, they reported on the “first cure for diabetes”, which does not accurately reflect the reality. The article explained how the research group used a novel protocol to generate insulin-producing beta cells from the patient's own cells. This is significant because, in people with diabetes, these pancreatic beta cells are the ones that lose their functionality. Their implantation was also performed unusually: using the abdominal wall instead of the liver, as had been done previously.

For more than a year now, the patient has been able to successfully manage his blood glucose levels without insulin injections. This is a major achievement.

However, it is essential to consider all the details of this case. Firstly, it is a unique case which has evolved over only one year. We must continue to learn from the experience of other cases and over a longer period of time.

In addition, the case is especially atypical. It is a patient with type 1 diabetes but compounded with a serious liver disease from another cause. In fact, the patient had to undergo a liver transplant and subsequently receive immunosuppressive treatment to minimise the risk of organ rejection.

Moreover, this patient had already undergone a pancreas transplant only 5 years after diagnosis, due to the diabetes being very difficult to control. During the 2 years in which the transplant was functioning, the claim could also have been made that he had been “cured”. Unfortunately, after this time the transplant failed and his situation once again became unstable. This is in fact why the patient was considered for inclusion in this experimental project.

What stage is the current research at?

Numerous strategies such as pancreatic, renopancreatic, islet, haematopoietic progenitor transplants and other reprogrammed cell transplants have all cured cases of diabetes previously. Nevertheless, these techniques still leave some important questions to be answered; such as the risk of rejection and the recurrence of diabetes. Researchers are therefore exploring options to modify or encapsulate transplanted cells to address these issues.

The significant advantage of using the patient's own cells is the reduced risk of rejection, thus avoiding immunosuppressive treatment, which has significant associated risks.

However, using cells very similar to the patient's own cells increases the risk of the immune system again attacking the insulin-producing organ or tissue.

Both scenarios were different for the patient described in the article due to the immunosuppressive treatment received for the liver transplant. Thus, the situation in this case makes it very difficult to generalise to normal type 1 diabetes cases.

Given these complexities, this case cannot be seen as the first definitive cure for type 1 diabetes; nor can the approach be broadly applied to a large population with type 1 diabetes.

To summarise, it is clear that cell therapy for restoring insulin secretion is one of the most advanced methods for the definitive treatment of diabetes. However, at the moment it is considered only in clinical trials reserved for patients with a complex medical history; fortunately, this situation is becoming less common.

Information documented by:

Dr Antonio Jesús Blanco, Endocrinologist, Clínic Institute of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases.