Short term memory is very limited in capacity and duration. An international study led by Albert Compte, principal researcher at the Systems Neuroscience group of the Institute of Biomedical Research August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, determined for the first time that short-term memory does not decay after the information is no longer visible but that neurons continue to represent it with increasingly less accuracy. This leads to the degradation over time of the memory accuracy. That is, the brain maintains information even when we think the memory is gone due to inaccurate responses. The results are reported in the scientific journal Nature Neuroscience. The first author of the study is Klaus Wimmer, also from IDIBAPS.

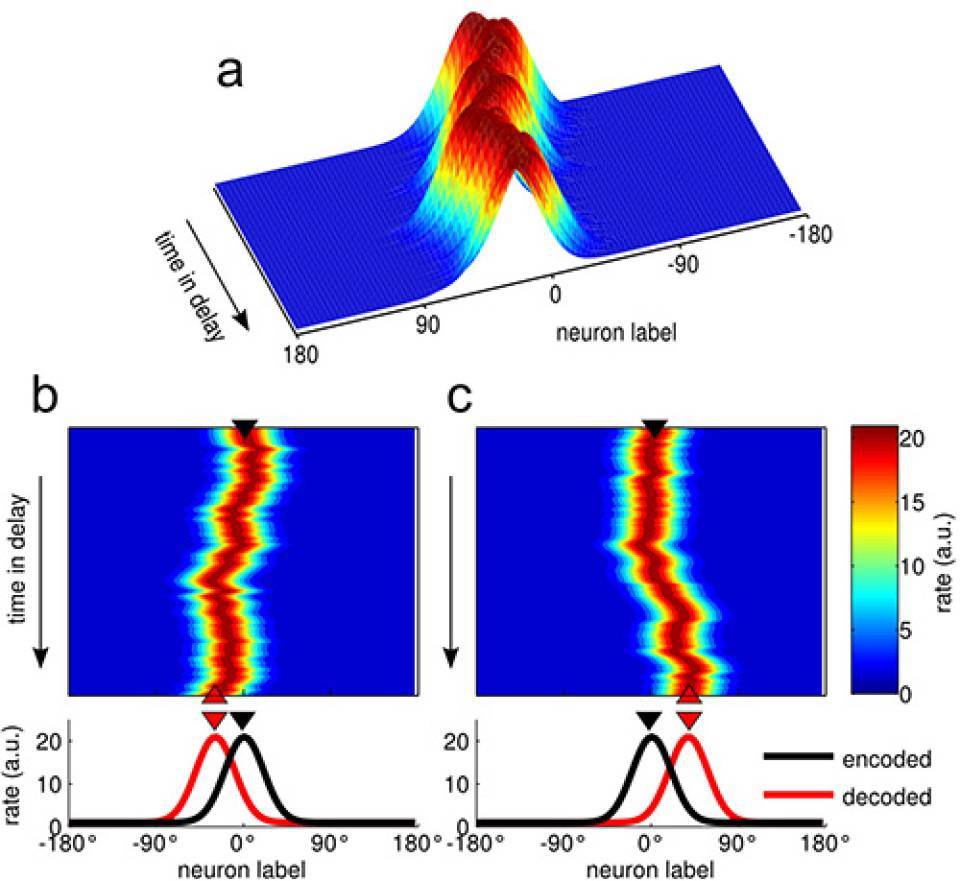

To explain how this memory is lost, the researchers used a computer model called Bump Attractor, which allows the computer to simulate the process of loss of information in the prefrontal cortex. This model suggests that neurons are active as memory degrades. "The activity diffuses in the neural network and the reported memory ends up being different from the stimulus, is distorted", says Albert Compte. "Distortion occurs through the dispersion, not loss of this activity. Previously it was thought that memory decayed, we now know that neurons remain active but lose stability", he explains.

The work is a collaboration with Duane Nykamp at the University of Minnesota and Christos Constantinidis at the Wake Forest School of Medicine in North Carolina, who provided brain activity data from two monkeys performing a working memory task. This work analyzed the activity of neurons, relating it to the behavior of the animal during the task. This has allowed for the first time to relate neural activity in the brain with the process of working memory decay. The findings of this study enhance our understanding of the mechanism of neural activity in working memory in the prefrontal cortex, which might help to understand what happens in mental illnesses like schizophrenia where short-term memory is impaired .

In the 70s Spanish researcher Joaquim Fuster first discovered in monkeys trained to perform simple tasks that neurons were active during the period of working memory maintenance. Subsequent studies showed that we lose precision of working memory for longer delays. This study identifies the neuronal basis of this loss of precision, and concludes that neurons maintain information but lose accuracy in representation.

Why is working memory important?

Working memory is the system that manages information to interact with our environment, allowing us to make immediate decisions or to structure speech. We are continually making use of working memory as we relate external and internal stimuli to future actions.

The main functions of working memory are maintaining information, reinforcing learning, understanding the environment at any given time, formulating immediate goals and problem solving.

Through this study, we now know that neurons have information on how the memory is lost, and we learn that information is continuously maintained in prefrontal cortex, even when memories appear gone due to loss of accuracy.

Article Reference

Klaus Wimmer, Duane Q Nykamp, Christos Constantinidis & Albert Compte, Bump attractor dynamics in prefrontal cortex explains behavioral precision in spatial working memory. Nature Neuroscience (2014) doi:10.1038/nn.3645