Psychologists and neurologists invest considerable effort in the study of working memory. In terms of information retention, there is a difference between long-term memory, which is affected in diseases such as Alzheimer, and short-term or working memory, which allows us to make immediate decisions or structure a discourse. This more ephemeral memory is affected in diseases such as schizophrenia and depression, although a cause-effect relationship has not been established. People with a higher working-memory capacity score higher on intelligence tests and, for this reason, it is thought that it may be intimately linked to people’s cognitive ability. A study by IDIBAPS uses computational systems neurobiology models and functional magnetic resonance imaging scans to show that there are two parts of the cerebral cortex with highly differentiated roles implicated in this type of memory. The results of the study will be published tomorrow in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), in an article headed by Dr. Albert Compte of the Systems Neuroscience team of the Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), and with Fredrik Edin as the first author. This study was carried out in collaboration with two other laboratories of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, led by professors Torkel Klingberg and Jesper Tegnér.

Thanks to complex computer algorithms, it is possible to simulate a virtual network in which a large number of neurons interact. These models can simulate the functioning of the structures in our brains. According to the computer model published in PNAS, when the working memory needs to be increased, the prefrontal cortex reinforces the activation of the parietal cortex, in which the information is temporarily stored. A brief stimulus that reaches the parietal cortex generates a reverberating activation that maintains a subpopulation active, while inhibitory interactions with neurons further away (lateral inhibition) prevents activation of the entire network. This lateral inhibition is also responsible for limiting the mnemonic capacity of the parietal network. The reinforcement of the parietal cortex by the prefrontal cortex prevents its inhibition, thereby temporarily improving working memory.

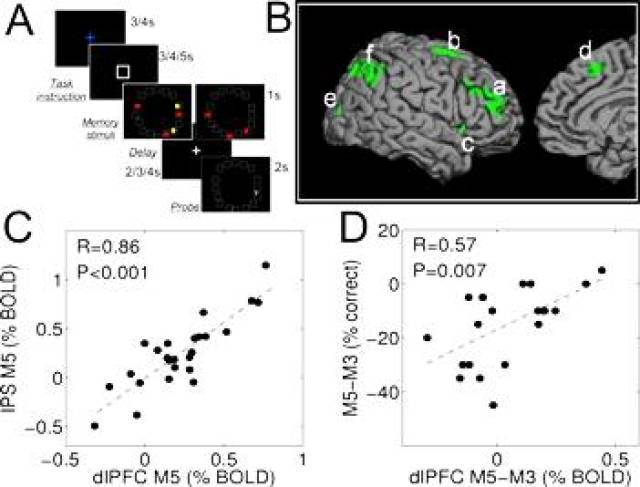

To verify this hypothesis, 25 healthy individuals carried out simple visual-memory tests while inside a functional magnetic resonance scanner. The differences in their ability to complete the exercises were linked to the intensity of activation of the prefrontal cortex and to their interconnection with the parietal cortex. The IDIBAPS researchers thus confirmed the hypothesis formulated based on the computer model. The more the prefrontal cortex is activated, the greater the capacity of the parietal cortex for retaining short-term visual information - an indicator of working-memory capacity.

This study explains many diverse results that have been obtained in recent years in psychology and neuroimaging studies on working memory. This is an innovative view of the neurobiological mechanisms of cognitive control and opens up new lines of research. Clinical studies will be needed to determine whether the stimulus of the prefrontal cortex, or its training by means of memory exercises and games, can have an effect on diseases in which working memory is damaged, such as depression or schizophrenia.