- What is it?

- Signs and symptoms

- Diagnosis and tests

- Treatment

- Evolution of the disease

- Living with the disease

- Research lines

- Frequently Asked Questions

-

La enfermedad en el Clínic

-

Equipo y estructura

What is the pituitary gland tumour?

A pituitary tumour is a lesion located in the pituitary gland. The majority of pituitary tumours are pituitary adenomas (estimated at 95%) that originate from the cells of the pituitary itself. They are practically always benign and slow growing, with only a small percentage extending into neighbouring structures.

he pituitary is a gland the size of a pea located at the base of the brain, just behind the nose. It secretes and regulates some of the main hormones found in the body, such as those related to development, sexuality and metabolism. The pituitary gland is associated with diseases such as acromegaly, gigantism and Cushing’s disease.

Pituitary Tumour explained in first person

Pituitary tumours must be operated on in situations where the tumour is growing and compressing the optic nerves. The post-op phase of pituitary tumour surgery is usually tolerated very well.

The first month and a half I was pretty worried, but then they said it was an adenoma and they calmed me down saying that “they are usually benign”, so it wasn’t cancer.

Craniopharyngiomas and meningiomas are also pituitary tumours. Other non-tumorous pituitary lesions are the vascular lesions (haemorrhages, aneurysms, etc.), inflammatory (hypophysitis), infectious (pituitary abscess, tuberculosis…), or cysts. Pituitary metastases (metastasis in pituitary of tumours of other origins) are rare.

The majority of the pituitary adenomas are usually benign and have a low level of growth. Small adenomas are generally found in the sella turcica, just behind the nose, although it is not uncommon to find these small and medium-sized tumours infiltrating the cavernous sinus. On the other hand, there are the invasive adenomas that have a more aggressive course, with a tendency to grow rapidly and invade structures like the carotid arteries and optic nerves.

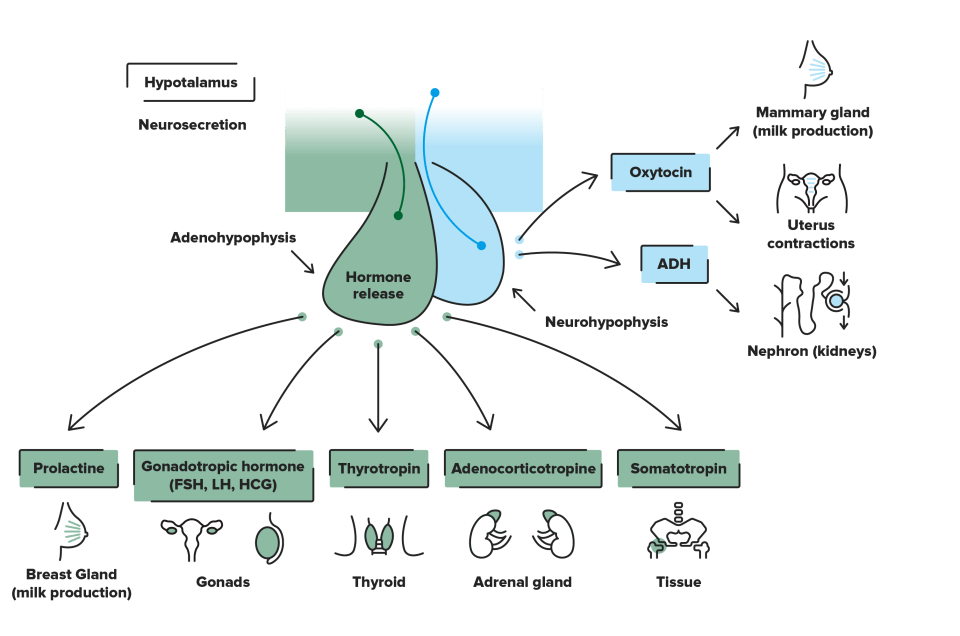

The pituitary and the production of hormones

The pituitary, also called the hypophysis, is a gland situated in the sella turcica, and is considered the principle gland of the endocrine system. It has a coordinating function that collects the messages from the brain and uses this information to produce hormones that stimulate and regulate other endocrine glands (thyroids, adrenals, gonads – testicles and ovaries-) and segregates hormones that act directly on essential biological functions such as growth, body water balance, or partum and lactation.

It is situated at the base of the skull, behind the bridge of the nose, in a bone depression that is called the sella turcica. It weighs approximately half a gramme, and measures about 10 mm wide x 6 mm from the anteroposterior axis x 5 mm in height. This is connected by the pituitary stalk to the hypothalamus, which is part of the brain. The optic nerves (involved in the sight) pass above the pituitary and their nerve fibres cross (optic chiasm). The sphenoid sinus is in the lower edge, which is the usual entry route by the surgeon in pituitary surgery. The cavernous sinuses are at the sides, where the vascular and nerve structures are found.

It is formed by two lobes: the anterior lobe, or adenohypophysis, and the posterior lobe, or neurohypophysis.

- The anterior lobe produces 6 hormones:

- Growth hormone (GH). It acts over the entire body and at liver level it induces the synthesis of somatomedin-C, or IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1). It is essential for growth in childhood and adolescence and for maintaining health, muscle mass, and energy in adults.

- Prolactin. It acts on the mammary glands, inducing lactation. Its levels increase physiologically during pregnancy and lactation.

- Thyrotropin (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, TSH). It acts on the thyroid glands stimulating the synthesis of thyroid hormone, or thyroxine. Thyroid hormone is essential for all the physiological functions of the body.

- Corticotropin (Adrenocorticotropic hormone, ACTH). It acts on the adrenal glands, stimulating cortisol synthesis.

- Gonadotropins (luteinising hormone –LH- and follicle stimulating hormone –FSH-). They act on the ovaries in females and the testicles in males, controlling sexual and reproductive function. They act on the ovaries, stimulating the production of oestrogens and progesterone, and inducing ovulation, as well as on the testicles for the production of testosterone and sperm.

- The posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis) releases 2 hormones that are produced in the hypothalamus and that, conducted by the pituitary stalk, are stored in the posterior pituitary until they are released:

- Oxytocin. It acts on the uterus, increasing the strength of the contractions during the final phase of childbirth (partum) and acts on the mammary gland, stimulating lactation.

- Anti-Diuretic Hormone (ADH), or vasopressin. It acts on the kidney, regulating the amount of urine that is eliminated, favouring the re-absorption of water.

When the peripheral hormones are present in an adequate amount, they act upon the hypothalamus and pituitary so that these slow down the production of their hormones, and with this, the quantity of peripheral hormones decreases. This mechanism is called negative feedback, and ensures that the quantity of circulating hormone is adequate, neither excessive nor insufficient.

Types of pituitary tumour

It can be classified:

- Depending on the size. They are classified as micro-adenomas (when they measure 10 mm or less) or macro-adenomas (they measure more than 10 mm).

- Depending on their capacity to produce hormones. They can be classified into functioning and non-functioning. The non-functioning adenomas do not produce hormones and, in general, the symptoms arise from the growth of the tumour and the compression of the neighbouring structures, or to the decrease in the normal production of the pituitary hormones. The functioning adenomas produce one or several pituitary hormones, and the symptoms are associated with the excessive production of the hormone, as well as also having symptoms arising from the growth of the tumour and the compression of the neighbouring structures. The functioning adenomas can be classified depending on the hormone that they produce:

- Prolactinoma. Is the most common functioning adenoma. It is due to an increase in the secretion of prolactin. It is clinically manifested in women with a change in menstrual rhythm, galactorrhoea (spontaneous flow of milk from the breast) and a decrease in libido. In males it is associated with a decrease in sexual desire and erectile dysfunction.

- Somatotropinoma. It is due to an excess in the production of growth hormone, and is the causing factor of acromegaly when it appears in the adult, or gigantism when it appears in infants (the growth cartilages are open). The symptoms can be progressive, which can delay the diagnosis. The most characteristic are the gradual increase in the size of the hands, feet, and the jaw, with the appearance of coarse features (need to change shoe size, the rings or hats that before fitted well do not fit anymore…), growth of lips and nose, increased sweating, tendency to snore…

- Thyrotropinoma. They are thyrotropin (TSH) producing adenomas, giving rise clinically to hyperthyroidism due to the excessive production of thyroxin. They are very uncommon.

- Corticotropinoma. Also known as Cushing’s disease, and it is due to an excess in the production of corticotropin, or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Clinically, affected individuals tend to gain weight, with round or “moon face”, appearance of dark-red stretch marks, hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis…

- According to the level of invasion of neighbouring structures. As regards the level of invasion of the cavernous sinus, the tumours are classified into four Knosp grades, with 0 being the grade in which there is no invasion of the cavernous sinus, and grade 4 in which the tumour completely surrounds the carotid.

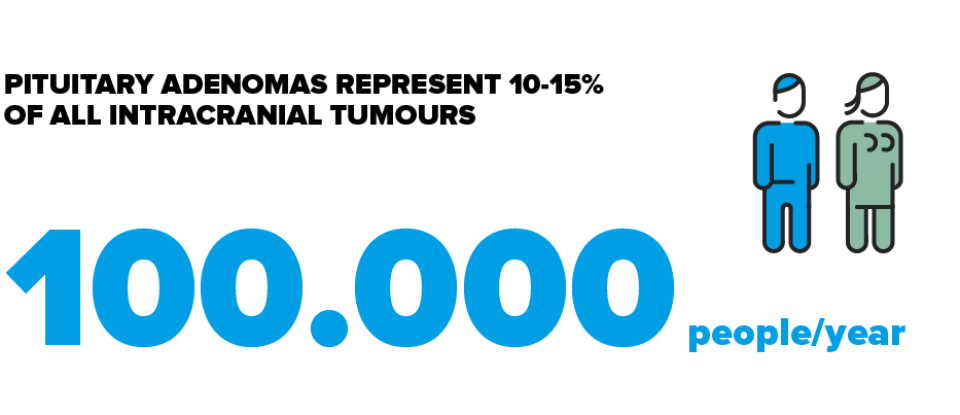

How many people are affected by a pituitary tumour?

Causes of Pituitary Tumours

They are sporadic in 95% of cases and the cause is unknown. The remaining 5% have a genetic cause, and are produced due to complex familial syndromes, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia types 1 and 4, Carney complex, or familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPA).

Substantiated information by:

Published: 20 February 2018

Updated: 4 September 2020

Subscribe

Receive the latest updates related to this content.

(*) Mandatory fields

Thank you for subscribing!

If this is the first time you subscribe you will receive a confirmation email, check your inbox