Every November, Clarivate Analytics publishes the list of Highly Cited Researchers, which identifies researchers who are among the top 1% of most cited researchers in their specialism. The 2021 list included 8 experts from Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS - and all 8 were men.

Weeks earlier, researchers from Stanford University published a ranking that identified the most influential researchers in the world in 22 scientific specialisms. In this case, there were 54 experts from Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS, of whom only 3 were women.

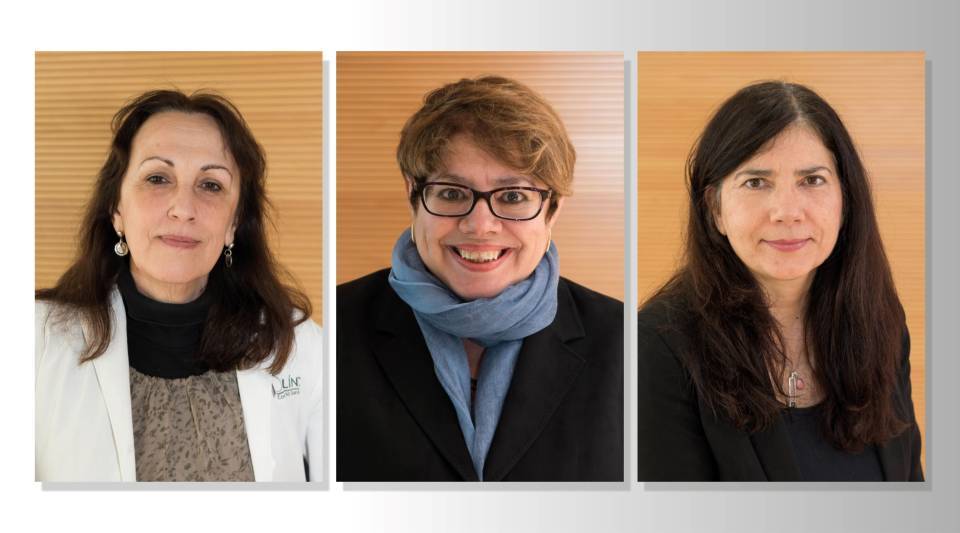

The three who are on the list explain why they believe that this imbalance exists and what can be done to promote equality. They are:

Mariona Cid, head of the Systemic vasculitis research group.

Mavi Sánchez-Vives, head of the Systems neuroscience research group.

Carme Junqué, head of the Neuropsychology research group.

Why are there so few women in scientific rankings?

Mavi Sánchez-Vives (MSV): these rankings are based on the citations accumulated over years and are not, therefore, a snapshot of the current situation; they reflect that of the 20 or 30 years ago, in which the vast majority of positions of responsibility were held by men.

Mariona Cid (MC): Women have found it hard to attain positions of responsibility, and we have arrived later. This delay in academic promotion is what we see in the rankings.

Carme Junqué (CJ): These gender differences are more marked in medical research than in other areas of knowledge, as the principal investigators on research projects are often heads of hospital departments or units – positions that, traditionally, have been held by men.

Will the situation change in the future?

MC: It will change, but it will take time. If we look at the weight of men and women throughout the scientific career, in many institutions, even today, the scissors graph is still the same: there are many women at the base, but few in positions of responsibility.

MSV: Undoubtedly, 20 years from now, the rankings of the most cited researchers will reflect the current situation and there will be far more women.

CJ: The generational shift will also result in more women in positions of responsibility and, therefore, also in the scientific rankings.

Have you experienced problems in your scientific career because you are a woman?

MC: Absolutely! Especially at the beginning. I have seen hostile heads of departments who did not want women on the staff, or who would straight-out tell you that an academic career was not compatible with being a wife and mother. And I have seen how men, in general, have been promoted more easily than women.

CJ: I have always had the feeling that I had to work twice as hard as a man to achieve leadership, to get promoted, to become a department head, to become the chair, to be principal investigator, etc.

MSV: In my case, I don’t think I’ve been discriminated against when obtaining grants or funding. I haven’t felt that I’ve received unequal treatment at an institutional level because of being a woman, but I have experienced it from people. Some anecdotes can be very revealing: you go to a meeting with a doctoral student from your group, and they talk to him as if he’s the leader, and you’re the student. Or they address men as “Professor” or “Doctor” and they call you by your first name. This is very common, and not just in science – it also happens with journalists. It seems like women have to make an extra effort to be given the same treatment as a man.

Do situations like these still occur today?

MSV: There is the well-known case of Ben Barres, a neuroscientist who transitioned from a woman to a man. After transitioning, he noticed that those who did not know he was transsexual treated him with more respect than when he was introduced as a woman. After giving his first seminar as a man, one scientist said that he had given a great seminar and that his work was much better than that of his sister, thinking that Barbara, his name as a woman, was his sister.

MC: Now nobody would dare say that women are not suited to research; there is no open discrimination, but small, everyday instances of sexism still exist. These are small, often unconscious attitudes that both men and women have without realizing it because they are so fundamentally part of us. We have, or we suffer from sexist attitudes, and we are not aware that they are sexist. You can still sometimes see instances of paternalistic treatment of women. Some heads talk to women in a condescending tone that they would never use to talk to a man. And in some cases, when delegating, a head will choose a woman for a certain task, but if something needs to be done that involves visibility and representativeness, they prefer a man.

And how does motherhood affect a career in science?

CJ: Having children has an enormous effect on your research career. It is not just the time you are on maternity leave, which many grants and projects now take into account, but everything that comes afterwards. A woman with small children has a much harder time holding a postdoctoral post, it is harder to attend conferences, where relations with other groups are often consolidated and relationships with publishers of scientific journals are facilitated. From that point, women have fewer opportunities to become principal investigators on projects because they have not been able to publish sufficient material during maternity or while the children are young.

MSV: A career in science is like an obstacle course, especially in our country. It is difficult and demanding, for both men and women. You often have to move around, with little job security; it’s a highly competitive world and funding is insufficient... This makes it very hard to combine with family life.

MC: Women tend to put family before the job more than men. If you add to this the fact that the research environment can sometimes be hostile, that as a woman, you have to dedicate more energy than a man in order to show that you are good enough, it means that many women decide to give up.

And what measures can scientific institutions such as IDIBAPS take to deal with this situation?

MSV: It is important that they draw up equality plans, as I know that IDIBAPS is doing, to break the glass ceiling. They then have to include measures that help to achieve a work-life balance. I also believe that women researchers need to be given visibility, especially young women.

CJ: There is often little that research centers can do about it. In Spain, we are going backwards in terms of the length of maternity and paternity leave in comparison to other countries, for example. I’m not a believer in quotas, but it is necessary to create the right conditions for equal opportunities. I think that we are moving in the right direction and that we will achieve equality within a few years.

MC: I agree that positive discrimination is not necessary, but we do need to avoid the small-scale, everyday sexist attitudes and this is something we all need to do: not just the institutions; each of us must be aware of them, identify them, and educate so that they are not repeated.

What would you say to a young female researcher about the subject of gender?

MSV: I would tell her to show her worth and not tolerate any kind of discrimination just because she’s a woman. And if she is looking for a partner, she should find someone who will understand and value her dedication to research. And if she wants to have children, she should look for institutions that are flexible and facilitate this.

CJ: She should be patient, plan her career carefully, and choose a partner who can accept equality.

MC: She should hold onto her self-esteem and self-confidence. A career in science is like a roller coaster, with good times and bad times.

This content has been writen with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology (FECYT).