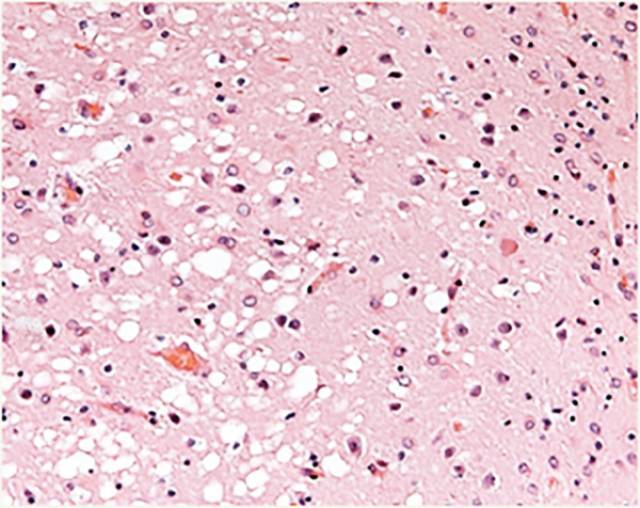

Prion disease, or transmissible spongiform encephalitis, comprises a group of rare and fatal neurodegenerative disorders that affect humans and other animal species. These diseases are thought to be caused by the abnormal folding of the prion protein, which is highly abundant in the neurons. Incorrectly folded forms of these proteins are called prions. Prions are infectious agents that can transmit their abnormal folding and transform normal prion proteins into pathologic forms. The propagation of prions from one cell to another causes damage to the cerebral tissue and the onset of symptoms characteristic of prion disease.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease, fatal familial insomnia (FFI), and kuru are examples of prion diseases.

In humans, most cases are sporadic. Nevertheless, between 10% and 15% have a genetic origin and fewer than 1% are acquired through exposure to tissue infected with prions. Patients with genetic or hereditary forms of the disease develop the first symptoms in middle or late adult age. This makes it possible to study the changes that take place in the brain before clinical manifestation, and to intervene before or during the initial stages of the neurodegenerative process. At present, however, there are no reliable markers for predicting the age of onset of the disease in persons at risk or for identifying onset of the disease in the brain. Furthermore, we have no biomarkers for monitoring the effect of potential treatments.

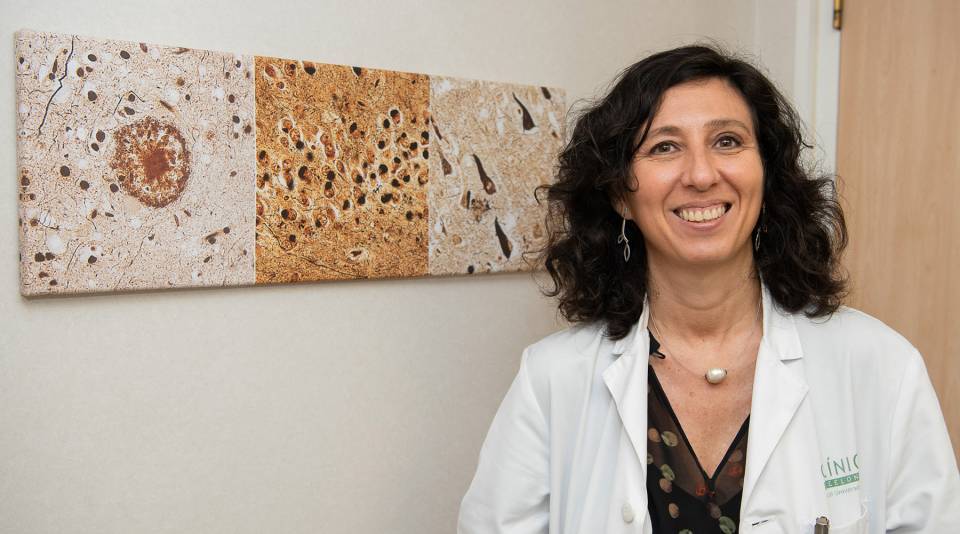

Researchers at Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS, led by Raquel Sánchez-Valle, head of the group Alzheimer disease and other cognitive disorders and of the neurology department, are carrying out a project, funded by the Dr. Josep Baselga fund. The objective of the study is to find markers for identifying, characterizing, and monitoring the neurodegenerative process, as well as new therapeutic targets. “Our goal is to generate evidence and tools for designing quality clinical trials that will allow us to test new drugs. To this end, over the next five years, we will use state-of-the-art technology to study a cohort of Spanish individuals at risk of developing genetic prion disease. We will also analyze data from sporadic cases, as we aim to extrapolate the results we obtain in these patients”, explained Sánchez-Valle.

Late diagnosis of people with sporadic prion disease and the rapid evolution to the fatal outcome makes it difficult to include these patients in clinical trials. “In the hereditary form, however, we know that the individuals are born with a genetic abnormality on the PRNP gene and that they will not develop the disease until the fifth or sixth decade of life. This gives us more time to study how and when the alterations that cause the disorder begin and how the disease progresses”, said the researcher.

The team has considerable experience in cohort studies of other hereditary neurodegenerative disorders, such as autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease and genetic frontotemporal dementia. “These studies drive clinical drug trials, as they provide highly valuable data that makes it possible to design viable protocols that can produce conclusive results. Moreover, despite the difficulties, over the years, we have shown that it is possible to obtain groups of patients affected by these rare diseases”, said Sánchez-Valle.

The group of researchers will carry out different types of data analysis. “Transversal studies estimate the magnitude and distribution of a disease at a given moment in time, whereas in longitudinal studies, observations are conducted repeatedly over time. That is, the former give us information on the state of the patient, for example, at the start of the study, whereas the latter allow us to monitor the course of the patient over months or years”, explained the researcher. “The transversal or longitudinal studies in the project will be prospective. This means that they will begin before the disease develops. Nevertheless, we will work with retrospective samples from the Hospital Clínic Barcelona-IDIBAPS biobank, from patients already diagnosed and with symptoms”.

Sánchez-Valle and her team expect to be able to recruit 50 participants over the five years the project will last. Over this time, they will assess the clinical and cognitive status of the participants. They will also ask them to provide samples of blood and cerebrospinal fluid, as well as a magnetic-resonance imaging study, every two years. In patients who develop symptoms, clinical assessment and collection of biologic samples will be performed once a month, provided that the individual can tolerate it. Moreover, the researchers will have access to the collection of samples of prion diseases from the Biobank, which contains 174 samples of blood serum, 330 samples of DNA, of which 33 correspond to genetic cases, and 250 samples of cerebrospinal fluid.

Finally, given that some recent evidence suggests the involvement of epigenetic modifications in some neurodegenerative diseases, the researchers will also analyze the differences between the epigenetic profiles of the sporadic and hereditary cases. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, mark certain parts of the chromosomes with molecules that function as switches and control the activity of genes, but without altering the information they contain. Epigenetics is the result of the influence of environmental and life-style factors on gene expression. Differences in DNA methylation between the genetic and sporadic forms of the prion diseases may help to determine whether the observed changes are the cause or consequence of the neurodegenerative process, as well as their link to ageing.

The team of researchers is profoundly grateful for this initiative of the Baselga family and to all the members of his family who have contributed to funding this project.