The treatment involves using a modified version of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae, removing its ability to cause disease and repurposing it to attack P. aeruginosa instead. The modified bacterium is used in combination with low doses of antibiotics that would otherwise not work on their own.

Researchers tested the efficacy of the treatment in mice, finding that it significantly reduced lung infections. The ‘living medicine’ doubled mouse survival rate compared to not using any treatment. Administering a single, high dose of the treatment showed no signs of toxicity in the lungs. Once the treatment had finished its course, the innate immune system cleared the modified bacteria in a period of four days.

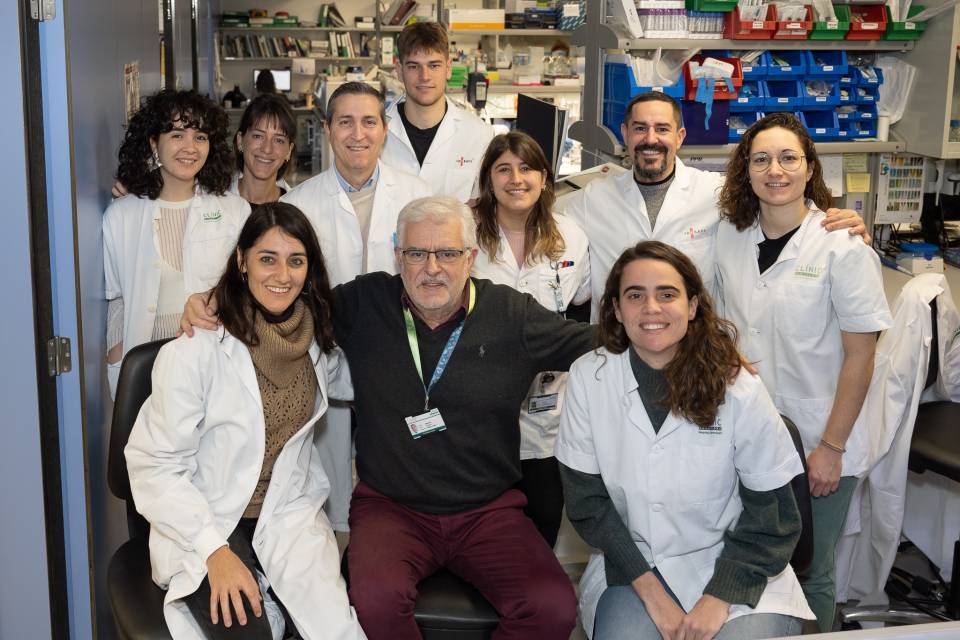

The study, published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, involved researchers from the Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS. In particular, Laia Fernández-Barat, coordinator of the research laboratory of the IDIBAPS Applied research in infectious respiratory diseases and critically ill patients research group, Ana Motos, coordinator of the porcine animal model, and Antoni Torres, head of the IDIBAPS group and senior consultant in the Hospital Clínic Pulmonology Service. The study was led by researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) and Pulmobiotics, and is supported by the ”la Caixa” Foundation through the CaixaResearch Health call. The Agrobiotechnology Institute (IdAB), a joint research institute of Spain’s CSIC, and the Government of Navarre also participated.

P. aeruginosa infections are difficult to treat because the bacteria lives in communities that form biofilms. Biofilms can attach themselves to various surfaces in the body, forming impenetrable structures that escape the reach of antibiotics.

P. aeruginosa biofilms can grow on the surface of endotracheal tubes used by critically-ill patients who require mechanical ventilators to breathe. This causes ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), a condition which affects one in four (9-27%) patients who require intubation. The incidence exceeds 50% for patients intubated because of severe Covid-19. VAP can extend the duration in intensive care unit for up to thirteen days and kills up to one in eight patients (9-13%).

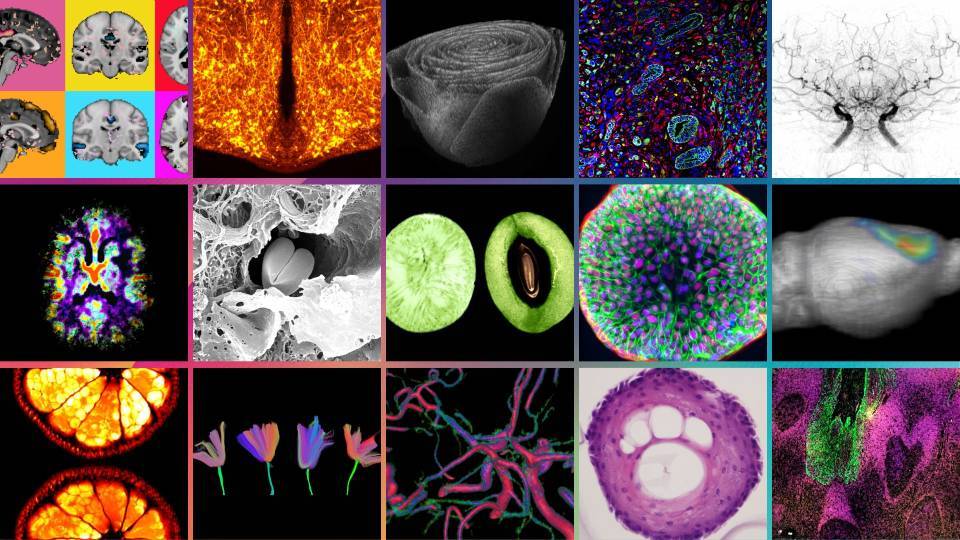

The authors of the study engineered M. pneumoniae to dissolve biofilms by equipping it with the ability to produce various molecules including pyocins, toxins naturally produced by bacteria to kill or inhibit the growth Pseudomonas bacterial strains. To test its efficacy, they collected P. aeruginosa biofilms from the endotracheal tubes of patients in intensive care units. They found the treatment penetrated the barrier and successfully dissolved the biofilms.

“We have developed a battering ram that lays siege to antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The treatment punches holes in their cell walls, providing crucial entry points for antibiotics to invade and clear infections at their source. We believe this is a promising new strategy to address the leading cause of mortality in hospitals,” says Dr. María Lluch, Chief Scientific Officer at Pulmobiotics, co-corresponding author of the study and principal investigator at the International University of Catalonia.

Dr. Antoni Torres’ group has a research line dedicated to biofilm-associated infections, which is led by Dr. Laia Fernández-Barat. "This model has allowed us to study real biofilms as they are during the intubation of a critically ill patient, adding an important translational value to the 'living medicine’”, explains Laia Fernández-Barat, who has described biofilms in endotracheal tubes after various therapeutic and preventive strategies. “Endotracheal tubes are normally discarded at patient extubation, but we keep them in a unique collection to study the biofilms,” she adds.

With the aim of using the ‘living medicine’ to treat VAP, the researchers will carry out further tests before reaching the clinical trial phase. The treatment is expected to be administered using a nebulizer, a device that turns liquid medicine into a mist which is then inhaled through a mouthpiece or a mask.

M. pneumoniae treat lung infections

M. pneumoniae is one of the smallest known species of bacteria. Dr. Luis Serrano, Director of the CRG, first had the idea to modify the bacteria and use it as a ‘living medicine’ two decades ago. Dr. Serrano is a specialist in synthetic biology, a field that involves repurposing organisms and engineering them to have new, useful abilities. With just 684 genes and no cell wall, the relative simplicity of M. pneumoniae makes it ideal for engineering biology for specific applications.

One of the advantages of using M. pneumoniae to treat respiratory diseases is that it is naturally adapted to lung tissue. After administering the modified bacterium, it travels straight to the source of a respiratory infection, where it sets up shop like a temporary factory and produces a variety of therapeutic molecules.

By showing that M. pneumoniae can tackle infections in the lung, the study opens the door for researchers creating new strains of the bacteria to tackle other types of respiratory diseases such as lung cancer or asthma. “The bacterium can be modified with a variety of different payloads – whether these are cytokines, nanobodies or defensins. The aim is to diversify the modified bacterium’s arsenal and unlock its full potential in treating a variety of complex diseases,” says ICREA Research Professor Dr. Luis Serrano.

In addition to designing the ‘living medicine’, Dr. Serrano’s research team are also using their expertise in synthetic biology to design new proteins that can be delivered by M. pneumoniae. The team are using these proteins to target inflammation caused by P. aeruginosa infections.