The IDIBAPS Cortical circuit dynamics group, led by Jaime de la Rocha, studies neural circuit mechanisms linked to cognitive functions such as perception, decision-making, and memory. Behavioral markers are measurable parameters whose alteration can be useful for the diagnosis, evolution, and treatment of various mental disorders.

“What we do in the lab is to train rodents, both rats and mice, to perform complex cognitive tasks, such as classifying auditory stimuli into two categories, learning the statistics of a sequence of stimuli or memorizing an action in order to carry it out after a period of time”, says De la Rocha. “Once the animals have learned these tasks, we implant electrodes in their brains to measure neural activity while they carry them out. This enables us to link the action or decision taken by a rodent to the activation of a specific group of neurons. When you use the same process in a model of a mental illness – for instance, a mouse with a genetic modification that might be similar to schizophrenia – then you can link behavioral deficits, such as memory problems, to the neural circuit alterations that cause these deficits. This is an approach with enormous potential”.

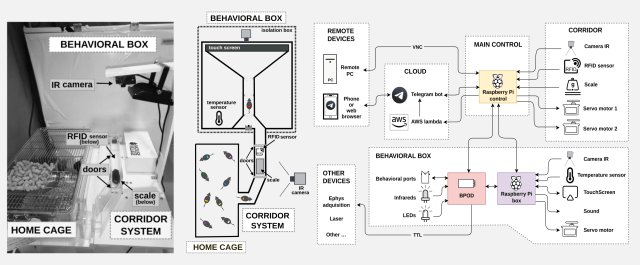

However, teaching mice to carry out these types of tasks is a long and complex process. Training sessions of an hour a day for two or three months are sometimes required. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the animals will finally learn to perform the different actions. For this reason, during the implementation of the ERC-CoG-2015-PRIORS Consolidator project, which receives funding of two million euros, the researchers designed and developed a platform where the rodents could be trained automatically, without the need for human intervention. “The mice live in their cages, but they can enter and leave the training box whenever they want. Via a chip implanted under their skin, the computer records entry and activates the appropriate task and level of difficulty for the animal. In other words, this is individualized training, as each mouse has its own learning speed”, explains Balma Serrano, pre-doctoral researcher in the group.

Over the next 18 months (the duration of the new project), the researchers will focus on improving the platform, which is known as Mouse Village. “We want to standardize a series of electronic components so that other laboratories can use it”, says Rafael Marín, the group's programmer and machine engineer. “Firstly, we will optimize both the implementation of the devices and the software needed to program them. Next, we will test the platform, training the mice in standard cognitive tasks commonly used in neuroscience. Finally, we will distribute the software as a commercially available open source system available to the entire scientific community”.

De la Rocha, Serrano and Marín highlight particularly the translational potential of the project, as it may help to resolve one of the current limitations in the process of developing new drugs for mental disorders: the lack of an automatic method to train and assess behavioral changes in animal models over time.